BOLIVIA – Climbing the Andes...

One adventure, two weeks time, three mountains to climb!

A Cultural Report about the Indigenous People of Bolivia

An expedition is not only about climbing mountains - it is a journey into far away countries with fascinating culture and traditions, it is also about the people. From the Bolivia tour in 2010, Touriosity Travel mag published a cultural report about the indigenous people of Bolivia in their March Issue 2013.

The native Quechua and Aymara have a strong believe in mountain gods and spirits of their ancestors living on the mountain peaks. Mountain gods are called “Apus” and offer protections to the people.

When the Inca conquered one mountain kingdom after another in their expansion along the Andes highlands, they ascended the highest peaks where other

tribes believed their mountain gods to reside. From the summit the Inca could be closer to their sun god “Inti” and built platforms with altars on the peaks to bring human sacrifice and

worshipped their god.

On my trip over the Altiplano to the southern tip of Bolivia bordering to Chile

and Argentine I visit temple ruins at the foot of Licancabur – the “Mountain of the people”. The summit is home to a crater

lake which is considered to be the highest lake in the world at 5.920m. On the rim of the summit crater I find well known wall remains as well as old firewood of Inca heritage.

For their sun cult and their belief in Inti, their sun god, the Inca might have climbed the highest peaks of the Americas 500 years before Alpinism was invented, an incredible achievement at that time.

The complete expedition report:

BOLIVIA – Climbing the Andes...

One adventure, two weeks time, three mountains to climb!

In search of our next travel destination Bolivia drew my interest. One of the quaintest countries along the Andesoffers everything I am looking for: Some of the highest mountains along the massive volcanic chain of the Andes and an incredible diversity of indigenous culture. The plan is to climb three mountains of around 6.000m in height in three different mountain ranges of the Bolivian Andes altogether within two weeks time. The target peaks are Uturuncu in the Cordillera Sud Lipez, Licancabur in the Cordillera Occidentaland Huyana Potosi in the Cordillera Real. Ticket booked and the adventure starts. Next Stop: Bolivia!

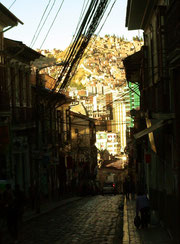

And the first step out of the plane already makes me breathless. Coming from my home town at 80m above sea level, the international airport of La Paz is situated at a dizzying height of 4.050m, surrounded by an

incredible panorama of peaks like Illimani (6.438m) and Huayna Potosi (6.088m).

The city itself spreads from the valley ground at 3.600m up the steep cobble stone roads over the mountain slopes to 4.150m

at El Alto. At this height in Europe one

would stand on the summit of some of the highest mountains of the Alps. But here in Bolivia it is just the starting point of my tour and a perfect beginning for acclimatization. Since reaching such heights without prior acclimatization has a severe risk of acute

mountain sickness with its various forms from serious headaches to lethal cerebral and pulmonary

oedema, I have to take it slowly. No matter how fit you are walking up the steep slopes of the town on the first day exhausts you quickly without being adjusted to the heights.

Here in La Paz I meet up with my climbing mate Jens, who has been trekking in Peru in the previous weeks for acclimatization.

Now we want to start our climbing tour together.

The city of La Paz is the vibrating economical capital of Bolivia. No doubt, the colourful bustling street markets are the pulsating heart and soul of the city, reflecting the country´s 60% majority of indigenous population. The biggest ethnics groups are Aymara, descendants of the Tihuanaco, and Quechua, descendants of the Inca. The native people cherish their traditions, culture, dances and clothes. Women wear the typical chola dress made of a colourful skirt, worn over several layers of petticoats. Aymara women wear brown, black or grey bowler hats different to Quechua women with their flat topped hats and their skirts are shorter.

Both wear their dresses as everyday clothes, for work as well as festivals, no matter how cold it is. And in the high Andes it can get artic cold! And the chola dress is worn by market sellers as well as business woman and even by politicians.

On the second day I go for an acclimatization daytrip to Chacaltaya, a mountain of 5.400m height dwarfed by the neighbouring peak of Huayna Potosi. You can drive up as far as the hut of the Club Andino at 5.200m since this area once was the world´s highest developed ski area. Nowadays the glacier is dying. I trek up the last couple of hundred vertical meters. The body needs to adjust to this height and movement is needed for this. By moving slowly you can reduce the risk of exhaustion and acute mountain sickness. Sleeping at this height on the second day is way too risky for me, so I return to La Paz to sleep lower. Still I get quite a headache in the evening – mate de coca, a tea brewed from the leaves of the coca bush is said to be a help for acclimatization. But it actually is just the fluids that are needed by your body. So I drink loads of tea to reduce

my headaches. For the next day I organize a bus ticket to travel into the most southern tip of Bolivia bordering to Chile and Argentina. It is a cold and bumpy 10h night ride over the highlands of the Altiplano. Early in the morning of the next day I step out of the bus and a bitter cold welcomes me to Uyuni at 3.800m, the last major town close to the giant salt lake Salar de Uyuni, the biggest of its kind.

Our time schedule is tight and we go immediately shopping for a rental jeep with driver for the next four days to reach my first two volcano peaks of Uturuncu and Licancabur.

At 5:00 o`clock we start our ride over the Altiplano, a country side that reminds me of a lunar landscape. An arid rock desert with volcanic craters and fumes, geysers and hot wells, huge mountains and lakes in all colours depending on the mineral deposits.

We stop for breakfast at Valle de Rocas, a scenic valley with bizarre rock formations, formed by erosion over millions of years. A snoopy Viscacha, a kind of mountain rabbit with a long tail from the family of the Chinchilla, accompanies us and certainly enjoys the crumbs of our bread.

We have to leave our new found friend behind and continue our ride to Quetana Chico (3.800m), a former mining settlement in the middle of nowhere that changed to a Lama herding town after the sulphur mine at

Volcan Uturuncu closed down. The 6.020m high twin peaks of Uturuncu irresistibly invite us from the far distance. Driven by the crazy idea to climb the mountain on the same day, we follow the old mining road that once led to the saddle between the two peaks. But the old jeep track is in a poor condition and suddenly it happens: an unsuspicious bank of snow drift turns out to be much deeper than we thought. Our jeep gets stuck in the deep snow at an altitude of around 5.000m.

In lack of a shovel we have to dig out the snow with our bare hands. It is a punishing job at this height.

We collect rocks and put them under the tires, just to see the jeep getting stuck in the following part. There is no chance to get any further by jeep and we lost a lot of time. Nonetheless I take my chances and start for the summit. Rather a none technical climb, but the steep and endless scree slopes alternate with snow drifts and teach you a new definition of pain and challenge your will to succeed. Every two steps you take it feels like sliding one step back again on the loose rocks. After each upswing you hope to see the summit, but there is just the next slope in view. And once you see the summit, it just seems not come any closer. My lack of acclimatization comes into account, my lungs burn and I can hardly control my heartbeat. All this comes with the unforgiving, arctic wind that whips your face and tears your clothes continuously. The sun is already pretty low when I reach the saddle at 5.700m. Foul sulphur fumes rise from the ground and form fumaroles and prove some activity of this volcano. But it is getting late, 17:30 already – just half an hour of sunlight left before the night closes in and temperatures make another deep drop. And still 300 vertical meters to go. I have to accept the fact that I will not be able to reach the summit in time. The risk to loose my way in the dark on the return is too high. So I turn back. We arrive in Quetana Chico late at night, eat a hot soup along with some tea and I think about the overhasty summit attempt. I did two major mistakes: the timing was bad, I was way too late on my approach and lost too much time and after just three days my body could not be adapted to the altitude, which slowed me down. You have to respect the altitude! Lesson learned.

We can not afford to spend another day for Uturuncu so we continue our ride towards Volcan Licancabur. On our way we witness the surprisingly rich wildlife of the Altiplano. I do not trust my eyes when I suddenly see an ostrich-like giant bird toddling in the arid rock desert. But it is real, a Nandu – the biggest flightless cursorial bird of the Americas! But I guess he is astonished by us visitors as well and runs for escape as quick as he can – and that is really fast.

We continue our ride over the lunar landscape with yellow, red, brown, blue, grey and black coloured mountains and volcanic cones to all sides. We stop at a steaming well and despite the biting cold wind we take a relaxing bath in this hot well in front of an amazing mountain panorama.

My driver meets another local on the stop. They exchange coca leaves and a kind of chalk powder. Chewing coca leaves is a common and popular habit in Bolivia, just like smoking cigarettes. But the coca leaf on its own has no narcotic impact – so does the plain tea of the leaf. That is why people chew coca leaves together with a chalk-like powder of limestone and ash that functions as an alkaloid that is needed to unfold the effect of the slight fraction of cocaine. In this reduced dose it is said to suppress appetite as well as fatigue and reduces influences of altitude. But I politely decline all offers. (When in La Paz, do visit the “Coca Museum” – an interesting view on facts from the traditional use of the past to today´s industrial use and misuse.)

All these old indigenous traditions make me think about their ideas about mountains, their gods and spirits.

Quechua and Aymara have a strong belief in mountain gods and spirits of their ancestors living on the mountain peaks. Mountain gods are called “Apus” and offer protections to the people. The eye-catching Illimani mountain that dominates the city panorama of La Paz is believed to be such an Apus, who protects the city. When the Inca conquered one mountain kingdom after another in their expansion along the Andes highlands, they ascended the highest peaks where other tribes believed their mountain gods to reside. From the summit the Inca could be closer to their sun god “Inti” and built platforms with altars on the peaks to bring human sacrifice and worshipped their god. This was one way to express their supremacy in religion and culture over the dominated tribes. From Peru to Bolivia and further into Chile and Argentina, more than 30 Inca mummies have been found on different peaks. On Chachani (6.057m), El Misti (5.822m) and Ampamato (6.312m) in Peru, El Toro (6.168m) and as high as Llullaillaco (6.739m) in Argentina, just to name a few. Even on the pre-summit of Aconcagua, Cerro Piramide, an Inca mummy has been found as a relict of human sacrifice for the Inca sun cult. Further up on the ridge connecting north and south peak, a guanaco corpus has been found at an altitude of around 6.900m. Guanacos were used as pack animals by the Inca. Since those animals would never climb that high on their own, it is quite possible that the Inca might have reached the highest summit of the Andes, Aconcagua with a height of 6.962m. However, a clear proof like a mummy or an altar has not been found on the main summit.

For their sun cult and their belief in Inti, their sun god, the Inca might have climbed the highest peaks of the Americas 500 years before Alpinism was invented, an incredible achievement at that time.

Our next destination, Licancabur mountain, is well known for Inca activities, as we are about to see by ourselves. Right behind the next pass, the aesthetic summit pyramid of Licancabur, “The Mountain of the People”(5.920m – latest NASA research measured the summit slightly above 6.000m), appears on the horizon, dominating the green and blue shimmering Laguna Verde below. The clear sky allows perfect light and enhances the wild mix of strong colours in this amazing panorama. On the shore of the lagoon at 4.400m is a hostel located where we stop for the night. At the foot of Licancabur we find

ruins of an Inca temple. Only the foundations of the wall remains still make the former size of the building visible. So from here the Inca started their conquest of Licancabur. The day ends with a beautiful sunset over Laguna Verde and mighty Licancabur mountain. We start from the hostel at 3:00 o`clock at night, passing the Inca ruins in the dark. Our route lies in the slipstream which makes temperatures pretty much bearable. We continue with good progress, it is just my diarrhoea that earns me some unintended stops.

The steep scree face alternates with snowfields. It is a beautiful moment when the sun rises over Laguna Verde and Laguna Blanca and touches our side of the mountain. But we do not have much time for a break to enjoy the incredible outlook. In the upper part we reach the gully and bigger block terrain. We pass a cross and a rock with memorial inscriptions that remind us of climbers that were not so lucky on this mountain and have lost their lives. Respect the altitude even when climbs are not so technical, is what falls into my mind again.

On several occasions we pass little heaps of old wood – in fact, fire wood that the Inca once left behind. We are close to the summit. And indeed we reach the summit shortly after, marked by Inca murals and fire wood on the crater rim. Now the full strength of the cold winds hits us on the summit, but we enjoy the incredible panorama over the surrounding mountains and lagoons. In close distance in the south-east we see the huge crater of Volcan Juriques (5.740m). Further to the south on Chilean ground appears the distinctive conical summit

of Cerro Pili also known as Acaramachi (6.046m) and many more peaks. From our birds-eye perspective the craters below remind us even more of the surface of the moon. The summit of Licancabur is home to a crater lake which is considered to be the highest lake in the world at 5.920m.

The lake was Subject of several scientific investigations even by NASA, since there were new species of zooplankton and bacteria found in the water. Life under these extreme environmental conditions with a much thinner atmosphere, extreme cold temperatures and a very high ultraviolet radiation, is comparable to other planets, especially ancient Martian lakes and could help to explain the evolution of life and its adaption to climate change.

On our way back down we use the steep parts with loose scree material to glide down with our boots like skiers. Of course this doesn’t always work out perfectly, a fall or two are the results, luckily without major scratches. But it certainly speeds up the long descent.

We hit the road again heading north along the Chilean border towards Laguna Colorada that we plan to reach by the end of the day. We pass the “Rocas de Dali” or Dali Rocks, huge boulders scattered over the high plain that reminds people of surrealistic paintings of Salvador Dali.

The jeep track climbs up to a pass of 5.000m before reaching the active volcanic geyser basin “Sol de Manana” at a height of 4.850m. Bubbling mud pots, steam clouds, geysers shooting into the sky under the pressure from the ground heat and sulphur fumes rising from craters really give you a feeling like standing on the moon, or better, in hell´s kitchen. We leave this inferno and continue our way to this mystical red lake when a wild herd of Lama crosses our path. We stop our jeep in watching distance.

At the next stop we reach the Flamingo colony at Laguna Colorada at 4.280m – a true oasis in the middle of the rock desert. The red colour of the water is the result of minerals and a special species of algae, a favoured feed of Flamingos. This makes Laguna Colorado to a popular breeding habitat of the Puna, the Andean and the Chilean Flamingo.

There is also a herd of Alpacas, the short-neck relatives of the Lama, grazing along the shore of the lagoon. Red and white threads on their ears mark them not as a free-living herd but as a breeder´s property. Since Laguna Colorada is a popular tourist spot we have no problem to find shelter in a simple hostel. The summit victory is fresh on our minds, so we celebrate our success with a decent beer and watch the sunset over the lagoon when the freezing cold sets in.

Main goal for the following day and last stage of our jeep trip is the Salar de Uyuni, the giant salt lake. On our 350km ride we pass the scenic landmark of “Arbol de Piedra”, a solitary rock formation shaped like a tree by the strong winds over the time. We continue through the “Inca Canyon” along a lake plateau with five lagoons of different colours according to the different minerals that occur here towards the smoking Volcan Ollague (5.865m), an active volcano with an old sulphur mine on the top.

Behind Volcan Ollague we meet a family of Vicunas, the shy Lama relative that only lives in the wild and can not live in captivity. They offer the finest fur, comparable to Cashmere and Pashmina – and as expensive since those rare animals can not be domesticated nor bred. Locals do battues with lots of noise to push them down from the mountains into the valleys sealed by fences. Here the animals get sheared before being released into the wild again.

We reach the blinding white Salar de Uyuni, the world´s biggest salt flat with the incredible dimension of more than 10.000 square kilometers. You totally loose your orientation and any feeling for distances, since there is no landmark, no point for orientation except one white plain from here to the horizon. This is a popular place for taking pictures of optical illusions. A person in the foreground looks like a giant while the person in the back seems to be a tiny dwarf. The true dimensions just disappear. We can not help but playing around with these visual tricks on photos.

In the middle of this sea of white salt a small rock island sticks out, Isla Incahuasi. The whole island is covered with impressive giant cacti that grow up to 12m tall and become as old as 1.200 years. I guess my cactus on my window board at home will never get to match those numbers. Before we leave the Salar we have a final stop at a specialty of the salt flat: A hotel completely built out of salt, from the walls to the roof, from the beds to chairs and tables. Everything is cut out of rock hard salt.

On our return to Uyuni we catch the next bus that brings us to La Paz overnight, from where we head to Zongo Pass at 4.800m in the Cordillera Real as our base for climbing Huayna Potosi. We spend two days and nights here. One day rest and the second we go ice climbing in the crevasses of the ice fall of the glacier. There is bad weather with strong winds, the summit is hidden by clouds. In hope for a weather change we ascend to a hut on 5.130m as our high camp. We are perfectly acclimatized now, the altitude is absolutely no problem for us anymore. We have the time and joy to watch the panorama from high camp. Below our stand point clouds move in and cover one peak after another like a thin veil of white. The weather seems to improve and we hope the best for the following day.

Summit day starts early at midnight when the first people get up. We start our climb at 2:30 following the normal route in the beginning. The glacier is smooth until we pass some crevasses and reach the first ice step that climbs just 50m to the eastern glacier. From here we can see the city lights of La Paz far in the distance below us – if you can see that far, the weather must be good today. We overtake the teams that started earlier than us and reach the Bergschrund. A nice snow bridge leads over the yawning abyss of the crevasse. Here we leave the normal route and prefer the little bit more interesting direct line over the east face to the summit, which towers immediately over us. This last pitch is just a 250m ice wall with a maximum steepness of 50 degrees that leads straight to the summit. At this moment the sunrise sets in and for a few minutes everything is soaked in deep orange while the sun rises as a red fireball on the horizon. We have perfect weather conditions with a clear deep blue sky. The last few meters of ice climbing above 6.000m get even more strenuous with the rising temperatures of the sun.

But we make it, victory is ours! The summit is more of a sharp ridge than a pyramid peak. We hang on to the summit ridge and enjoy the moment with a fascinating panorama over the complete chain of the Cordillera Real. In the south we can see Illimani (6.438m) and in the north all the way to Ancohuma (6.427m) and Illampu (6.368m).

On the return we use the normal route over the sharp north ridge – like on a razor´s edge, just some icy 50cm wide with a drop of 250m to the east and a sheer 1000m free fall into the west face make you balance your feet carefully one after another. With this stunning view it is one of the nicest ridges I ever walked.

We descend all the way to La Paz on the same day. For the last days we inhale the fascinating mix of traditional indigenous life, modernity and Spanish colonial atmosphere. Delicious Bolivian food with Lama steaks, mate de coca and decent beer are a perfect finish for an adventurous trip.